Added By: valashain

Last Updated: Administrator

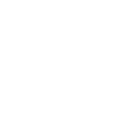

Sacred Ground

| Author: | Mercedes Lackey |

| Publisher: |

HarperCollins/Voyager, 1995 Tor, 1994 |

| Series: | |

|

This book does not appear to be part of a series. If this is incorrect, and you know the name of the series to which it belongs, please let us know. |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Fantasy |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

Jennifer Talldeer is Osage and Cherokee, granddaughter of a powerful Medicine Man. She walks a difficult path: contrary to tribal custom, she is learning a warrior's magics. A freelance private investigator, Jennifer spends hours tracking down stolen Indian artifacts.

The construction of a new shopping mall uncovers fragments of human bone, revealing possible desecration of an ancient burial ground. the sabotage of construction equipment implicated Native American activists--particularly Jennifer's old flame, who is more attractive, and more dangerous, than ever. Worst of all, the grave of Jennifer's legendary medicine Man ancestor has been destroyed, his tools of power scattered, and a great evil freed to walk the land.

Jennifer must stand against the darkness. If she wavers even for an instant, she will be annihilated, and the world will fall into oblivion.

Excerpt

Chapter one

She poured a dipperful of water over the hot rocks in the heaterbox, and steam hissed up in sudden clouds, saturating the dimly lit sauna with moisture. The smoke of cedar and sweetgrass joined the steam, the humidity making both scents so vivid she tasted them in the back of her throat.

She sat down cross-legged on the wooden floor, boards that had been sanded as smooth as satin underneath her bare thighs. It didn't matter to her--or more importantly, to Grandfather--that this sweatlodge was really a commercially made portable sauna; that the rocks were heated by electricity and not in a fire; that the sweetgrass and cedar smoke were from incense bought at an esoteric bookstore in Tulsa. Or even that the sweatlodge as a place for meditation was more common among the Lakotah Sioux than the Osage; Grandfather had borrowed judiciously from other nations to remake the ways of the Little Old Men into something that worked again. The destination is what matters, he had told her a thousand times, and the path you take to get there. Not whether your ritual clothing is of tradecloth or buckskin, the water you drink from a stream or a spring-or even the kitchen tap. Sometimes ancient ways are not particularly wise, just old.

So they had this contrivance of the I'n-Shta-Heh, the "Heavy Eyebrows," installed in what had been the useless half-bath at the back of the house she and Grandfather shared. Most of the time it served as nothing more esoteric than anyone else's sauna, useful for aching muscles and staving off colds.

Sometimes it served purposes the I'n-Shta-Heh who built it would never have dreamed of. She closed her eyes, sweat salty on her upper lip, and stripped off the layers of her working self the way she had stripped the layers of her working clothing before she had taken her ritual bath and entered the now-sanctified wooden box. There were layers to who she was, like an onion, each layer both hiding the one beneath and keeping the one beneath from reaching outward.

Jennifer Talldeer. The face that the white world saw; ironic name for a woman a shade less than five feet in height. Doubly ironic considering how tall Osage men and women tended to be. Your mother's genes, was what her father said, when she asked him why she was the runt of the litter. That sneaky Cherokee blood. You know how they are. With no acrimony; no one in her family believed in refighting old battles. Her mother had just smiled.

Private Investigator, degree in criminology. Nice little house, nice little neighborhood, nice little mortgage, in one of the older parts of Tulsa. Nice old neighbors, who thought it charming of her to take in her aged and "infirm" (ha!) grandfather. That persona was the first to go, washed away in the steam.

Next, the woman who danced at the powwows, engaged in her little hobby of rescuing sacred objects from profane hands; another mask, just one a little closer to the truth, a little deeper to the bone. A woman who bore two names, one for the earth-people and one for the sky-people, although it was the latter she used. Hu-lah-to-me, Good Eagle Woman, daughter of Hu-lah-shu-tsy, Red Eagle. Good Eagle was not registered on either side of her family, Osage or Cherokee, but she and her family had more right to call themselves Native American than plenty who were registered and could speak of no more than a single grandparent of the full blood.

Fly away, Good Eagle. Gone; there wasn't much there anyway. Jennifer was what she did; Good Eagle was simply an intermediary between what she did and what she was.Last layer; what she was.

The third Osage name, a name that was learned and not given. Kestrel-Hunts- Alone.

Not a "normal" name for a woman.

Kestrel, pupil of a man with three names, her grandfather. His Heavy Eyebrows name, Frank Talldeer. His second, quite out of keeping with the Tzi-Sho, and a name embodying contradiction, Ka-ha-ska, White Crow. And his third--embodying even more contradiction than the first--Ka-ha-me-o-pah, Mooncrow; crows do not fly at night, nor are they associated with the moon, and those birds that do fly at night are generally the enemies of crows. The power of the Osage centered on the sun, not the moon; a man of power should have had a sun-name, like her father's. Contradiction piled on contradiction....

Shamanic apprentice to her grandfather, her spirit-name was taken from her spirit-animal, student as she was in the teaching of one of the Little Old Men of the Ni-U-Ko'n-Ska, the Children of the Middle Waters, whom the Heavy Eyebrows and Long Knives called "Osage." By birth and by spirit, she was gentle Tzi-Sho gens, the peacemakers, and here lay the irony, for not only was Mooncrow teaching her the peaceful medicine of Tzi-Sho, he was teaching her the medicine of the warriors, the Earth People, the Hunkah. And, as if that were not enough, he was teaching her the special medicines reserved for each of the clans! For that, she had thought, one had to be a Medicine Chief and not simply a shaman. Grandfather had never once come out and said that he was--

Then again, maybe he was simply living up to his contrary nature. He wasn't registered, either; nor were any of his forefathers. And he wouldn't use any of the Peyote rituals that had crept into, and indeed supplanted, most of the Osage ways; they were like kudzu or mimosa in the red-clay soil--not native, but once there, impossible to get rid of. He had certainly been teaching her things no tradition she knew of called for; he had adopted the Lakotah sacred pipe; and he was passing to her the medicines of virtually every Osage clan from Bear to Otter to Eagle, things she thought were kept as clan secrets.

That would be like him; the man who cheerfully used an electric sauna for a sweatlodge, who prepared sacred tobacco in a fruit-dryer bought at an ex-hippie's yard sale, who purchased his cornmeal for ceremonies at the big chaingrocery--

Who taught a woman Warrior's Medicine.

Kestrel realized where her thoughts were leading her, and resolutely brought her concentration back where it belonged. This Seeking was not about Mooncrow, but about herself. About her progress, or rather, lack of progress.

There was something holding her back, and she did not know what it was. Mooncrow would not tell her, saying only that if there really was something holding up her progress, she already knew what it was; typical contrary reasoning. She wondered where he'd gotten that particular mind-set; it wasn't typical for Osage Medicine. And it certainly made life difficult for his student. She could have used a teacher less like Coyote and Crow, and more like Buffalo and Eagle. Simpler instruction, fewer tricks; more straightforward direction, fewer riddles.

He's doing it to me again. Making her annoyed, taking her thoughts off the path. To be honest, making her angry. He had chosen to teach her, and how he taught her was his choice, not hers. It was her duty, her privilege, to learn. If she were failing somewhere, it was up to her to find out where and why, and correct it. Only then would she earn her medicine-pipe.

She let her temper cool, poured another dipperful of water on the rocks, saw that the cedar still burned, and started over, determined that Mooncrow and his contrary ways would not distract her again. He was "just doing that," like the buffalo, who did what they pleased, when and where they pleased, and if it seemed out-of-season, who would dare to stop them? Steam wreathed her, heat and semidarkness held her, and this time she slipped away from herself to fly among the other worlds, among the other Peoples of Water, Earth, and Sky.

It was in the Sky she found herself, a sky blue and cloudless to the east, dark and cloudy to the west, with Grandfather Sun on her back and wings, and the heat of thermals off the prairie below bearing her up. She flew above the meeting of forest and prairie, with the oaks and redbud, cottonwood and willow stretching into the east, and an endless sea of tallgrass to the west.

If she had worn human shape, there would have been the hot, dry scent of grasses carried by the thermal she rode, but raptors have no sense of smell, and all that came to her through her nares was the heavy, drowsy heat.

She flew in the shape of her Spirit-Animal, the kestrel of her name. A good shape, one suited to swift travel, although if she had hopped like Toad or crawled like Turtle, the results would have been the same--those she needed to have counsel of would have found her, if she had not been able to travel swiftly enough to find them. That was the way it was; the Wah-K'on-Tah saw to it, in whatever ways it suited the Great Mystery to work. If, however, she chose to perch and wait--she would never find those wise counselors. And it wasn't a good idea to tempt other, smaller mysteries into action against her by being lazy.

So she flew, low over tallgrass prairie, until movement below sent her up to hover as only kestrel, of all the falcons, could.

Rabbit looked up at her from the shadows at the base of the grass, his nose twitching with amusement. "Come down, little sister," he offered. "Come and tell me what you seek, out of your world and in mine."

She stooped and landed beside him, claws closing on grass stems as if they were a mouse. "An answer," she said, folding her wings with a careful flip to align the feathers properly, for a raptor's life depends on her feathers. "What is it that keeps me unworthy to become a pipebearer? Where have I failed?"

"I am not the one to ask," said Rabbit. His pink nose quivered as he tested the air, constantly, and his gray-brown coat blended perfectly with the dead grass of last year. "You know what my counsel is; silence and care, and always vigilance. I do not think that will help you much. But perhaps our cousin in the grasses there can answer you."

He pointed with his quivering pink nose at a spiderweb strung between three tall grass stems and the outstretched branch of a blackberry bush. Spider watched her from the center of her web, swaying with the breeze; a large black and tan orb-spider, nearly the size of her kestrel-head. Rabbit accepted her word of thanks and hopped away. In a moment he had vanished among the grasses.

She repeated her question to Spider, who thought it over for a moment or two, as the breeze swayed her web and flies buzzed tantalizingly near. "You must know that I am going to counsel patience," she said, "for that is my way. All things come to my web, eventually, and break their necks therein."

Kestrel bobbed her head, though she did not feel particularly

patient. "That is true," she replied. "But it is more than lack of patience--I must be unready, somehow. There is something I have not done properly."

"If you feel that strongly, then you are unready," Spider replied,

agreeing with her. "I see that you do have great patience--except, perhaps, with your Grandfather. But he is a capricious Little Old Man, and difficult, and his tricks do not make you laugh as they did when you were a child. I think perhaps I cannot see what it is that makes you unready. Why not ask one with sharper eyes than mine?"

She wondered for a moment if there was a hidden message in that little speech about her Grandfather, but if there was, she couldn't see it. Spider pointed to the blue sky above with one of her forelegs, and Kestrel's sharp eyes spotted the tiny dot that could only be Prairie Falcon soaring high in a

thermal. Her feathers slicked down to her body in reflex, for the prairie falcon of the plains of the outer world would quite happily make a meal of a kestrel.

For that matter, if she let fear overcome her, Prairie Falcon of the inner world would happily make a meal of Kestrel.

But that was a lesson she had learned long ago, and the tiny atavistic fears of the form she wore were things she had overcome many times. She thanked Spider, who turned her interest back to a dewdrop threatening her web, and launched herself into the air.

* * *

She returned to the steam-laden sauna with no answers, only a load of defeat, and the surety that she was not only unready, she was unworthy. Not good enough.

And she still didn't know why.

Kestrel became Good Eagle Woman; Good Eagle Woman assumed the mask of Jennifer. She opened her eyes and stood carefully, feeling for the switch that turned the heaterbox off, then finding the door latch and pushing it open, releasing the steam into the air-conditioned cool of the hall.

There were old bathrobes hanging beside the sauna; she wrapped herself in one and headed for the shower.

As the hot water sheeted down her body, she tried to let it clear her spirit of depression. It didn't succeed, not entirely.

She should have been ready by now; she should have been good enough. She had mastered skills just as difficult in a shorter time frame--to save money, she'd gotten her four year degree in three years, while continuing to study the shamanic traditions. Not good enough; that hung in her chest, a weight on her soul and heart, pulling her to the ground when she wanted to fly. It was time--it was more than time. She had spent years in this apprenticeship; she should have been ready by now. She should have been good enough.

How long had she been doing this, anyway?

Since I was just a kid, she thought, trying to remember the very first time her grandfather had singled her out for teaching. Then it came to her--

* * *

"You see Rabbit?" Granpa asked her, coming up behind her on the white-painted back porch, so quietly he had made no sound. But she had known he was there. She always knew where he was; he was a Presence to the heart, like a little sun, a glow, always shining with energy and cheer.

She had been sitting on the porch for a while, just watching the birds at the feeder, when the little rabbit had crept cautiously up to help himself to some of the stale bread her mother put out for the crows and grackles. He couldn't have been more than two months old; no longer dependent on his mother, but scarcely half the size of a grown rabbit. He never stopped watching all around while he nibbled; never stopped swiveling his ears in every direction, alert for danger. His fur looked very soft, softer than her cat's, and her fingers itched to stroke him. But she knew that if she moved, he would be off in a moment.

She nodded, not speaking. Granpa wouldn't frighten the rabbit no matter what he did or said, she knew that, but she also knew she would. It was just a fact, like the green grass. Granpa could walk right up to a wild deer and touch it. She wouldn't be able to get within a mile of one.

"No, not just this rabbit--" Granpa persisted, "Rabbit."

She had not puzzled at the statement, as virtually any adult and most children would have. She heard what he meant, not what he said, and looked deeper--

That was when the half-grown cottontail became Rabbit, grew to adult-human size and more, sat up, and looked at her.

"Hello, little sister," he said politely. "Thank your mother for her bread, but ask her if she would put some of the kitchen greens out here for us as well, would you? Carrot-ends taste just fine to us, and bug-chewed cabbage leaves, or rusty lettuce. Crow might like a taste of carrot now and again, too."

Wide-eyed, she had nodded, noting how modest he was, how quiet; how he had made his thanks before making his request. It came to her then, right into her mind, how hard life was for him--how everything was his enemy. He not only had to flee his ancient foes of Hawk and Coyote, Rattlesnake and Fire, but the new ones brought by humans, Dog and Cat. And humans hunted him too--she'd eaten rabbit often, herself.

But he survived by being quiet, by skill at hiding and running, and by being very, very fruitful. He sired many offspring, so that one out of every ten might live to sire or give birth.

And he did well by being something of an opportunist. Now that the land had been covered with houses with neat backyards, there were alleys full of weeds to eat and hide in, and sometimes the kitchen rubbish to eat as well. There were spaces between fences and under houses or garages to make into warrens. Dogs and cats could be dodged by escaping into another yard, or under a porch. And of the hawks and falcons, only kestrels hunted among the houses

at all regularly. Rabbit had adapted to the world created by the Heavy Eyebrows, and now prospered where creatures that had not adapted were not prospering.

Just like us, she thought with astonishment. Just like Mommy and Daddy and Granpa--

Because they lived in a house in the suburbs of Claremore, because Daddy didn't get tribal oil money, he had a job as a welder, and that was the same for Mommy and Granpa, too. There was nothing to show that they were Osage and Cherokee except their name. They lived just like their neighbors, went to church every Sunday at First Presbyterian, and Mommy even had bridge club on Thursday afternoon--except, like Rabbit, they had a secret life of stories, traditions, and dances and special ceremonies that none of their neighbors knew about. They had their hiding places in between the "fences" and under the "porches" of the white ways, where they did their Osage and Cherokee

things--

Granpa had laughed, and Rabbit dwindled and became a half-grown cottontail, who had fled like a wind-blown leaf into the dark shadows under the honeysuckle.

That was when he had taken her by the hand, led her in to Daddy, who was finishing his breakfast, and said, "This one."

* * *

That was definitely it, the moment she had begun training at Grandfather's hands. There hadn't been many children her age in their neighborhood and there weren't any of them she really cared to hang around with; Grandfather had taken pains to make the training into games, and she hardly missed not having playmates. At some point, though, it had turned serious, no longer a game but a responsibility. She rinsed her hair with a torrent of hot water, wryly congratulating herself on putting in the biggest hot-water tank available. A small luxury, like the sauna. An advantage of being an adult with your own home--though when it came to responsibility, she had been an adult for years before she had moved out of her parents' home. Maybe they were both a little environmentally excessive, but she was frugal with her energy use in general, and she confronted her conscience with the stacks of recycling bins in the kitchen; she recycled everything, and food leavings went either to the neighbor's compost heap or to feed the birds, squirrels, rabbits, and freeloading cats.

There was no question when that turning point of adult responsibility in her lessons had happened; it had been at one of the powwows in the Tulsa area, and she had been thirteen.

* * *

Until tonight, the powwow had been a lot of fun. Dad had won the Traditional Fancy-dancer Contest, but although she had been urged to compete by several of her friends, Good Eagle had remained in the stands during the ladies' contests, held there by a growing feeling of tension. For now--there was something in the air, and not just the hint of the thunderstorm that usually put in an appearance every year during this particular powwow.

The ponderous heat of August, nearly one hundred today, had baked the area in and around the grandstands as thoroughly as if they were inside a giant oven. The grass lay parched and burned to soft brown, limp strands of fiber, with only a hint of green near the roots; the earth still radiated heat, cracked and baked flint-hard. That was one reason why the adult contests were always held at night--to prevent the participants from passing out with sunstroke. And although rain threatened, it had not fallen, and the arena lights made a haze of the dust raised by hundreds of dancing feet. Tonight there wasn't even a breeze to clear it away.

Something else weighed heavily tonight besides the heat; Grandfather felt it too, for he was unusually quiet. She kept looking around at the stands, wondering who or what it could be--then beyond the stands, up into the sky, where heat-lightning flickered orange behind the trees. Grandfather's hand took hers, and she started as a kind of electric charge passed between them.

It jolted her out of herself--but not into the other worlds. She was still in her own world, standing beside her body as Grandfather stood beside his. To any onlooker, they were only an old man and his small granddaughter, enraptured

by the dancers.

"Someone is trying to make trouble, Kestrel," Grandfather said. "Two someones, I think. One of them is white-he wants to cause a fight and blame it on the Peoples. But the other is Osage, he wants the fight too, but he wants it to get power over some of the young hotheads. That is what we feel. We must deal with both these young men."

"But Grandfather, how are we to stop this fight--like this?" she asked, puzzled. "Shouldn't the policemen take care of it?"

An innocent question; at thirteen, she had still trusted the police. She had still trusted in white man's justice. Grandfather had not disabused her of that--because he was wise enough to know that sometimes the wrongs were not entirely one-sided. Perhaps that was why she had gone into law in the first place....

"I will deal with the white boys; I am more used to this way of things than you are," he told her. "But I need a young warrior to deal with the other--" His eyes sparkled as he looked at her, and she knew that she was the one he meant. Excitement had made her shiver; this was an adult task. And Grandfather made it clear that she was to deal with this young man without supervision.

She saw then that he had his own medicine-costume on; it looked much like his dancing-gear, except that he carried his implements openly, not hidden in their pouches.

"He is taking peyote," Grandfather continued, a faint note of disgust in his voice. "He has taken it already, thinking it will help him dance better, to raise the power he needs to control and impress his friends. He has not even done it properly; he has not followed either the West Moon or East Moon Church ways; he has simply made up some nonsense of his own. He will be able to see you. You must go and stop him."

It never entered her head to tell him no. Grandfather was right; this was important. There had been trouble at this site before, and there were people who came to the powwows purely to harass the participants. The only way to get permission to use public land like Mohawk Park was to make the event open to the public; that meant open to troublemakers, too. Liquor was a problem, for people often brought strong alcohol with them; heat and hot tempers did not help in the least.

"He is down among the dancers, there," Grandfather said, and slid down under the grandstand, into a shadow. What came out of the shadow was not a human but a rangy old coyote, who gave her a hanging-tongue coyote grin and was gone.

If her responsibility was down among the dancers milling around the entrance to the arena for the next competition, that gave her an advantage. She only needed to go down there and walk among them in spirit. There was no reason for a woman to be in their company, and her target would be the only one who would notice her, since she would not be wearing her body.

No sooner decided than done; she dropped down under the grandstand and drifted through the crowd there to the place where the dancers had gathered. Then she walked among them, staring each one in the face.

They ignored her, intent on their preparations, unable to see her, except perhaps as a ghostly shadow.

All but one.

He glared at her, and looked ready to speak. She saw the peculiarly fixed stare of a Peyote-taker, and knew that he was the one her Grandfather had meant.

She gave him no opportunity to speak. Instead, she seized him by the wrist, and as he started in surprise and tried to resist, she stepped off into the other worlds, taking his spirit with her.

As she pulled his spirit from his body, she sensed his body collapsing; not too surprising, for Grandfather claimed that the Peyote-takers who did not follow the proper Ways relied on the drug rather than discipline to walk among the worlds, and as a consequence had no control over their bodies when they left them. He did not approve of Peyote at all, really, but he would not condemn others for using it if they were properly prepared, as this man was not. She had transformed herself as she stepped over the threshold; now she was no longer a little girl in a buckskin dress but a tall young man, modeled after her brother, in full warrior's gear. She sensed that this young man would not listen to anyone except someone he deemed stronger than himself.

He pulled out of her grip; she let him. He stood looking about, at the open prairie, full moon overhead, with no sign of humans in any direction he cared to stare. Slowly, his eyes widened, as he realized where he must be.

"You meant to cause a fight," she said flatly, knowing what he had intended without needing to ask him. "You just wanted to get on television, so you could look important to your friends. You tell them that you're a big civil-rights activist, but all you want is to look like a big shot. You've been telling them that you're a Medicine Person, a shaman, but you aren't a shaman; you're just a phony, a faker, and everything you do is just tricks and drugs."

If her accusations surprised him with their accuracy, he wasn't going to admit it. He simply crossed his arms over his chest, and she sensed he was going to try to bluff his way out of this.

"While you're pretending to have Medicine Powers, all you've done is have a couple of sweatlodges and taken a lot of peyote," she continued sternly. "You didn't even do the sweatlodges right, and you might just as well have gone to a health club instead."

He needs to learn a lesson, she thought. That is what Grandfather wants me to do--see that he gets it. He cares more for himself and what he can make people do than whether or not it is good for them--

That was when she realized who should deliver the lesson, and what it should be. As he regained his courage and turned a frowning face to try to bully her, she stepped back a pace, and transformed again.

This time, she wore the semblance of the She-Wolf, and she raised her nose to the moon to summon the Pack.

Howls answered her from all sides, and before the young man could blink, he found himself surrounded by the Wolves of the Pack, both the great gray timber wolves and their smaller cousins of the prairie, and even one or two of the rangy red wolves that were long gone from her world. They all stared at him with great yellow eyes, fur tipped with silver from the moon above.

"You called the Pack, sister," said the Pack Leader, gravely.

She bowed her head to him; as a female, she need not bare her throat in submission to a male. "I did, brother," she replied. "This is one who leads his pack into danger for the sake of his own ambition and prestige, and does not care what will befall them so long as his power is increased."

"So," said the Leader, turning his golden gaze on the young man, who shrank away. "You think perhaps I should challenge his right to lead, then?"

Again she bowed her head. "As you wish, Pack Leader," she replied humbly. "I am but a young female; I only know this one needs discipline."

The Leader grinned toothily. "Then discipline he shall have."

In a moment, there was a young Wolf where the young man had stood; another moment passed while he trembled with shock and surprise; then the Lead Wolf was on him, treating him as he would any young fool who dared to challenge him for the right to lead the Pack.

There would be no killing--oh no. But before this one was sent back to his body by the contemptuous fling of a pair of lupine jaws, he would be certain he was about to be killed, not once but a hundred times over. Likely, he would not again dare to reach for Medicine Powers he was not entitled to, with the help of peyote. Not after this experience.

Satisfied that the Lead Wolf had the situation well in hand, she stepped back across the threshold and into her own body, just in time to see the competition begin. Paramedics were taking the young man who had collapsed to the first-aid tent; they were probably assuming heatstroke. He would wake up soon--and with no more thoughts of causing trouble tonight, at least.

Grandfather's hand tightened around hers, and she looked up into his wrinkled, smiling face. "Well done," he whispered.

That was all. He never told her what he had done, but later her father told them a story he'd gotten from one of the Tulsa County Sheriffs, about a dog that had spooked the normally steady horse ridden by one of the mounted officers. The rangy dog--reportedly a German shepherd--had driven the horse right down a trail away from the powwow and into a gathering of young white boys who were carrying bats and chains, were drunk, and were obviously out to start a fight. The officer had rounded them up with the help of his suddenly cooperative horse, and had seen they were escorted out of the park--and had arrested the most aggressive for public intoxication. "Damndest thing they'd ever seen," her father had said, with a curious glance at Grandfather. "Those crowd-control ponies just don't spook. And to head in the right direction like that--"

Grandfather hadn't said anything, and neither had Jennifer. But from that moment, the games ended, and the serious work began.

* * *

From then on, she'd applied herself with the same determination that she'd given to her studies. There hadn't been much room in her life for anything else, particularly not once she started her sideline of "finding." The first time it had been by accident; she'd been working on a case that had taken her up to Indiana, tracing the movements of a child-support dodger. She'd found herself in a tiny town with four hours to kill, and had in desperation followed a sign that pointed the way to a "county museum."

"Museum" wasn't exactly what she would have called it. It looked more like the leavings of the attics for miles around for the past several generations. There was an attempt at outlining the county history in the first room, but after that, it had been dusty glass case after case full of mostly unlabeled flotsam. Without a doubt, some of it was genuine and valuable; the Civil War artifacts, for instance--

But right beside war diaries that screamed for proper preservation were stuffed squirrels, stuffed birds, stuffed fish...

...a mummified mermaid...a shrunken head...someone's collection of jelly jars...

And the relics.

She nearly doubled over with nausea; she couldn't even bear to touch the case. Scalps, medicine bags, articles of clothing, weapons, and three or four dozen skulls, all of them crying out to her of death. Bloody, horrible death. Kestrel had come very near to starting a mourning keen until the Jennifer persona took over.

She staggered to the front of the museum and managed to ask about that particular case. The attendant, a girl who was obviously trying to do her best, first described the terrible problem she was having, trying to preserve the things worth preserving with no money. She carried on at length about the importance of the papers and belongings of the settlers.

Gradually it dawned on Jennifer that this girl never said a word about the Indians; so far as she was concerned, the history of the area began and ended with the white settlers.

When she finally got the girl to tell her about the case of bones and artifacts, the girl shrugged dismissively. "Mound builders of some kind," she said. "Abram Vanderzandt found them when he arrived looking for a place to homestead, and they were all dead. Probably some other tribe killed them, and he could have taken credit and turned in the scalps for bounty, but he was an honest man and he just collected a few souvenirs."

The girl continued, apparently blithely unaware--or uncaring--that Jennifer was Native American, that she had dismissed the taking of "souvenirs" from the victims of the massacre as casually as if they had been nothing more important than the stuffed squirrels.

For a moment, Jennifer was outraged--until the girl continued. And it became clear that she attached sanctity to no one's dead, and would have happily looted every graveyard in the county if she thought she could get any kind of information from the graves.

And it was her attitude that only those who had left written accounts of themselves--the white settlers-were worthy of attention that gave Jennifer an idea.

"Well, the reason I asked about that particular case," she said, interrupting a plaint of how the Civil War relics were falling to pieces, "is that I collect Indian relics. I don't suppose you'd be able to sell me those, would you?"

The girl gaped at her, then stammered something about "county property." Jennifer nodded, and said, "So who's in charge of county property? The Assessor? Or the County Commissioner?"

It took several phone calls before it was established that the Country Commissioner did have the authority to sell property deeded to the museum. Jennifer was not going to let this opportunity slip through her fingers, and the volunteer was not about to lose a chance at some funding for her pet project. So when Jennifer urged, "Let's go ask him," the girl led the march straight to the tiny office on the fourth floor.

She had the feeling that she could have bought half the museum if she'd wanted; the Commissioner was overjoyed to sell something the girl assured him was "worthless." He was probably very tired of her pleas for money; now she had some, and maybe she'd leave him alone for a while.

Jennifer was fairly certain that the sale was only quasi- legal at best, and she hadn't cared. It was doubtful that anyone would pursue her.

It had taken every ounce of determination to take the box relics, smile, and thank them.

The place where the settler in question had discovered the massacre was now in the middle of a state park. That made things easier.

Whatever the tribe's rites had been, no one knew them now. Jennifer could only inter them near where they had died, trying to recreate a rite as best she could from her own intuition and Medicine knowledge, as well as from things she had learned about the Peoples who had once lived in the area, gleaned hastily from the county library. She found a place she thought would be undisturbed, one of the lesser, less interesting mounds near what had been the village, and spent most of the day digging into the side. At sunset, she had laid them to rest as best she could.

Then she covered her tracks, and went back to the job she was being paid to do.

But that had given her an idea. There were hundreds, if not thousands, of artifacts in profane hands, all over the country. Not just museums, but in the hands of people like private collectors, and in the hands of the descendants of Indian agents. Some agents had been good, well-intentioned, if woefully Judeo-Christian-centered people, but some had been thieves who took anything they could get their hands on, and others had felt the only way to "pacify" the Indians was to destroy their culture. Most of those artifacts didn't matter; much--but some--

For some, it would be as if collectors had robbed the tomb of Abraham Lincoln for the sake of the bones, or stolen the relics of Catholic saints out of their shrines. As it some museum knowingly bought the Black Stone after it was stolen from the shrine at Mecca. The remains of Ancestors deserved a proper interment--and medicine objects deserved to go back to the hands that cherished them. That was when she had decided that she would do something about the situation; tracking these objects down and returning them to the appropriate hands. There were plenty of people at work on the major museums, using publicity at lawyers to regain lost artifacts and remains; she would concentrate on getting the things back in the hands of private individuals. Grandfather had approved, and that was all she had needed.

It took time, but she had time--and what else was she doing with her life, anyway? Certainly there were no men in it. She might as well do something useful with her free time.

Now I'm getting depressed--no, I'm depressing myself on purpose, she decided. This is ridiculous. What I need right now is a good night's sleep.

She turned off the water and wrapped her dripping hair in a towel, bundling herself back up in a robe. A big glass of orange juice, then bed.

The living room was dark, the house locked up; Grandfather had gone off to bed himself already. She shook her head at the time; she hadn't realized it was that late.

But as she slipped in between the cool cotton sheets, she felt a familiar tingling that told her that her Seeking hadn't ended in the sweatlodge. She barely had time to settle herself before she found herself out in the Worlds again.

* * *

But this was no World she knew; the place was grim and frightening, calling up a feeling of disturbance inside her that made her feel a little sick.

Beneath a gray overcast sky, a dead, chemical-laden wind stirred the branches of withered trees planted in little sterile circles of hard-baked earth. Except for those tiny circles of dead ground, the rest was concrete as far as the eye could see. She turned, slowly, and saw nothing else; nothing but leafless trees and lifeless earth--a parking lot for the damned.

Then, beneath one of the trees, she saw, with an internal hock, the desiccated corpse of a bird.

Hesitantly, with her stomach churning, she approached it. In a moment she saw that it had been a bald eagle; it lay sprawled ungracefully on the bare gray concrete, lying in a way that suggested it had dropped dead--perhaps from poison--rather than being shot or knocked out of the sky. The harsh breeze stirred its feathers as she stared down at it.

Something about the eagle jarred a memory--hadn't there been something about that mall-project on the Arkansas River near the eagles' nesting site?

She looked up, suddenly, and realized what this World symbolized.

I've been concentrating so much of my attention internally that I've been ignoring my connections to my own World and what's going on around me. Maybe that's what's been holding me back...

As if she had somehow satisfied something--or someone--with that thought, she found herself moving out of that World and back into her own. She started to relax--

Then something dark, shapeless, and completely evil loomed up, interposing itself between her and the way back.

It looked at her for a moment, while she tried to shrink into something so small she could evade its gaze. The ploy didn't work; it reached for her, with eager, greedy interest.

Fear overcame her. She turned and fled.

Copyright © 1994 by Mercedes Lackey

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details