![]() Sable Aradia

Sable Aradia

7/10/2019

![]()

Read for the Science Fiction Masterworks Book Club.

"What a lovely book!" I said to my partner with a delighted sigh as I closed the cover, after having done nothing all day but glue my eyes to these pages, and turn them, one after the other, so quickly I hardly realized I was doing it.

I suppose, in part, I can be forgiven, because I am still sick. My neck still hurts (although less) and now I have a doozy of a cold to go with it.

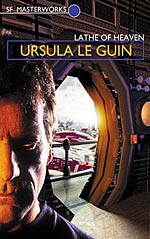

Fortunately, Le Guin's liquid, luminescent prose took me away from all that for a while, completely immersing me in her world where a man's dreams literally change reality.

Don't get me wrong. This is not a fairy tale. This is the Monkey's Paw. As Le Guin points out, the subconscious mind is immoral and illogical, and it's the subconscious that holds sway in dreams.

The trouble starts when a man is sent for "Voluntary Treatment" for drug abuse when he suffers from an overdose. Turns out he is trying to suppress his dreams, and the reason is that he has become aware that what he dreams becomes reality. Not all the time: just when a particularly deep, "effective" dream is reached.

The psychiatrist he is sent to, Dr. William Haber, is a dream expert who has invented a machine that uses brainwave entrainment to get a patient to follow a programmed sleep pattern. This psychiatrist genuinely means well, but his is the self-assured mentality of the scientific specialist or the Evangelical minister. He is convinced, through both his perception of his intelligence, and his belief in his own righteousness, that he knows what is best for everyone. When he discovers the truth of his patient's ability, he begins to consciously manipulate the patient's dreams in order to change reality according to his personal image of Utopia; with increasingly horrible results.

He is contrasted with the patient, George Orr, who is almost a non-entity. He would really rather just go along to get along, and is kind of a timid and mild-mannered man. But the juxtaposition between the two is fascinating. Although Haber seems strong, at heart, he requires constant propping to his ego; and George carries an internal reserve of amazing patience and strength.

Le Guin winds up the tension like a tourniquet; slow and hard. I literally could not put the book down, wondering what on earth was going to happen next! And the conclusion was deeply satisfying, as only a long journey, where you know the characters have suffered much, and both gained and lost, can be, even though it's a relatively short little book.

The contrast between this and the last book I read, VALIS by Philip K. Dick, could not have been greater. In many ways, it was like what would happen if Ursula K. Le Guin wrote Philip K. Dick - and according to some reviews here that I've read, that was the intent. Having researched it, I find no tangible proof of that, just speculation from scholarly works that are quoted in Wikipedia. But I could see it.

The plot reminded me quite a lot of Now Wait for Last Year, but the contrast in style could not have been greater. I find that while both writers are excellent in their critiquing of society, psychiatry, and the egotism of authority, Dick is full of nihilism, confusion, and despair. Instead, Le Guin's approach is overwhelmingly one of gentle chastisement, hope, and even a little whimsy.

My nature is more like Haber's than Orr's. I find it difficult to accept the world as it is. I always question and fight, always want to change things and make them better.

But do I really know what is best? Can I effectively visualize the unintended consequences of the changes I would make? Is there some point at which we must just accept what is, and embrace the mysterious without trying to understand it?

And yet, Orr's way, at least at the beginning of the book, is not the best way, either. He's afraid to take any responsibility or to make any changes. And how he discovered his ability was that when he was dying of radiation sickness in a starving, climate-changed world scarred by nuclear war, he dreamed that there hadn't been a war. Eventually he points out to the other characters that the ability has a purpose, but it should only be used when it is needed.

And how do you know when that is? As Le Guin tells us, you get by with a little help from your friends. We need other people to check ourselves against, especially those who are quite different from us. That might well be the most poignant scene in the whole book, and it's where we get one of Le Guin's legacy of brilliant quotes:

Love doesn't just sit there, like a stone,

it has to be made, like bread;

remade all the time,

made new.

And thus by reading this great work from a wise and beautiful soul who made the world a better place, I, too, am made new.

Up until now, my favourite book of all time has been Watership Down. I re-read it about once every five to ten years, and get something new out of it every single time, as age and maturity give me a greater appreciation of things I missed before. I expect this book will join that rare and precious category. I cannot recommend it enough.

http://www.dianemorrisonfiction.com